An Interview with Dr. Edward Machtinger: Lessons of Trauma-Informed Care

In this blog post, Dr. Meier is joined by Dr. Machtinger, Director of the Women’s HIV Program at UCSF. This interview provides a sneak peek into his keynote, “Trauma-Informed Care: A Case Study in Whole-Patient Care,” at CAPC National Seminar 2018.

Dr. Diane E. Meier (DEM): Thank you for agreeing to be a plenary speaker at CAPC National Seminar. Let’s start this interview by having you tell us what trauma-informed care is.

Dr. Edward Machtinger (EM): I’ll frame trauma-informed health care in the context of palliative care, and my evolving understanding of what that is; trauma-informed health care should be seen as a tool to realize the vision of palliative care. The guiding vision of palliative care, which I’ve learned from CAPC—the boldest that I’ve encountered in the field of medicine—is to see the person beyond the disease and improve their quality of life, and that of their family.

How do you see the person beyond their disease in a way that’s truly insightful, and that facilitates improving the quality of their life? One of the best ways I have found is to move from asking yourself what’s wrong with somebody, to asking what happened to them. For many people suffering from serious illness, being able to help them in the most meaningful ways requires understanding that what happened to them is serious trauma, whether in childhood or adulthood.

This understanding is important for those who practice palliative care, as so much of their work occurs in the context of a unique relationship—through connection. Understanding and addressing trauma in terms of connection, and helping to establish that connection, demystifies why so many patients have intractable health issues that lead to their serious chronic illnesses, like diabetes, despite receiving what we think are effective treatments. And why, in all forms and fields of medicine, substance use and chronic pain are so common, as well as why many forms of mental illness, like depression, anxiety, and isolation, are so prevalent and intractable.

Trauma-informed health care is based on three tenets

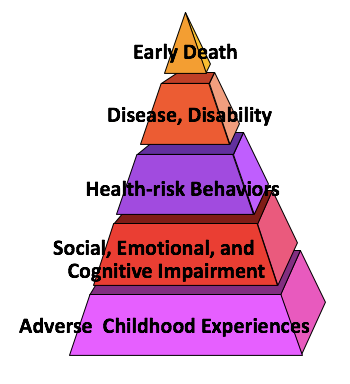

1) Childhood and adult trauma underlie and perpetuate many serious physical and psychosocial illnesses

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration defines trauma as, “an event, a series of events, or set of circumstances experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful, or life-threatening, with lasting adverse effects.”

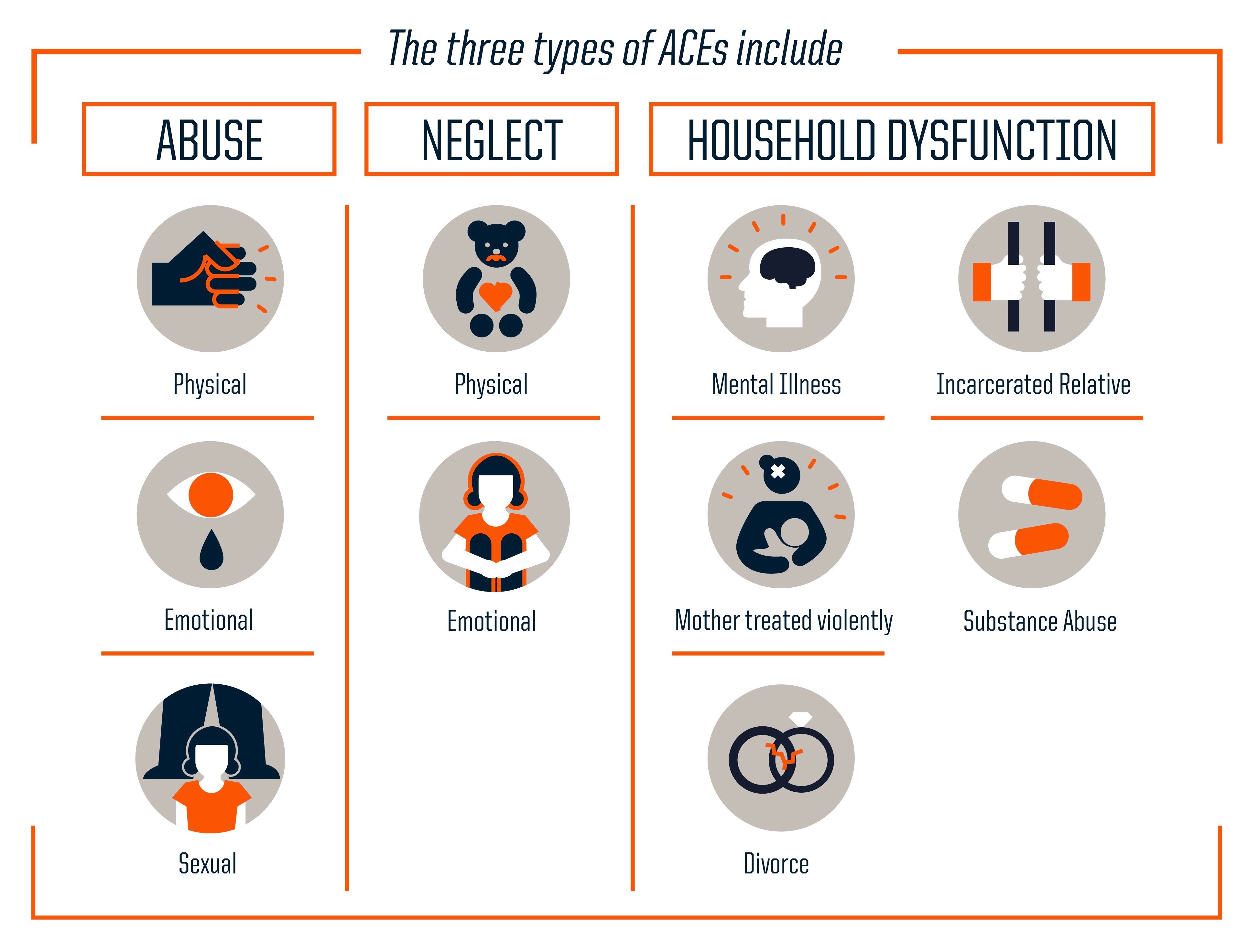

In my field, we include childhood and adult physical, emotional and sexual abuse, neglect, partner violence, and community violence. And in a way that is under-recognized in medicine, we also include the structural violence in our society, such as racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, and transphobia, among others. What I think is so powerful about trauma-informed health care is that we can help people cope with intractable traumas like structural violence or racism.

It’s important for palliative care providers to know that a serious medical illness is itself a well-known cause of serious trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder.

It’s important for palliative care providers to know that a serious medical illness is itself a well-known cause of serious trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. From the diagnosis to the aftermath, this experience is traumatic. As clinicians, we can ask patients, ‘what happened to you’, which not only validates our instinct to ask about peoples’ lives and experiences, but allows us to understand aspects of patients’ history. This allows for more time to talk with and be with patients, enabling the history to surface. I have found that it’s not necessary to directly ask people about their childhood trauma. Given an opening, demonstrated curiosity, and passion, the trauma and its impact will emerge.

2) Data shows that there is a striking association between trauma and illness

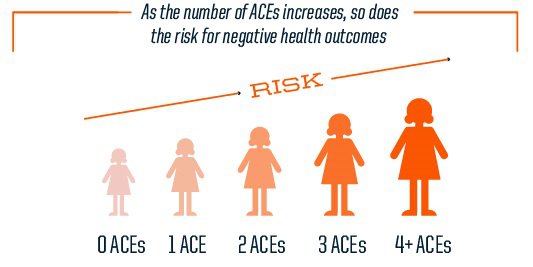

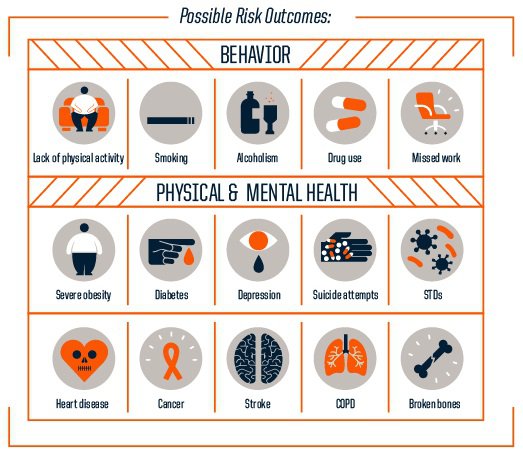

The best known and most compelling literature has to do with childhood trauma, now better known as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The seminal ACE study provides estimates-of-odds ratios for having conditions in adulthood if a person has experienced ACEs in childhood. The study shows that ACEs in childhood are strongly correlated with adult disease. For example, people who have experienced four or more categories of ACEs have 2x the rate of lung and liver disease, 3x the rate of depression, approximately 3x the rate of alcoholism, 11x the rate of intravenous drug use, and 14x the rate of attempted suicide.

3) Effective, evidence-based treatments exist, which can be integrated into health care settings and palliative care teams to help people heal from trauma and its consequence, PTSD

It is possible to make real, meaningful differences in peoples’ lives, despite them having experienced crushing trauma. Most of the trauma-related conditions that we are facing are more effectively treated if trauma and PTSD are understood and addressed. Many obstacles to effective connection have to do with mental illness and substance abuse. This is most effectively overcome if trauma is acknowledged and trauma-specific treatments are offered, along with more typical treatments for substance use or mental illness.

It is possible to make real, meaningful differences in peoples’ lives, despite them having experienced crushing trauma.

In my field of HIV, where we’ve had antiretroviral medicines since 1996, HIV itself is no longer the primary issue affecting peoples’ suffering and death. It is trauma and the consequences of trauma. When I look at the last nine deaths of my patients, they were from murder, substance-related overdose (2), substance-related organ disease (2), suicide (2), pancreatic cancer, and then a young 22-year old woman who stopped taking her antiretroviral medicines and died of a preventable opportunistic infection. In other words, she died from depression and hopelessness. We’ve come to see HIV, this huge, life-defining illness, as a symptom of a bigger problem, which is childhood and adult trauma. We were missing the impact of trauma because we weren’t taught [in medical or nursing school] what trauma is, or that trauma can be successfully addressed within the health care environment. Understanding the impact of trauma was ignored in our training despite its central role in illness and suffering.

DEM: There was an interesting study recently that asked a representative sample of physicians what they thought was the role of social determinants of health in their patients’ health and medical well-being. Everyone agreed that social determinants were the major driver of poor health and suffering. They were subsequently asked what they thought their role was in addressing these—more than 90 percent said it was not their responsibility. What are the risks to patients of bringing these issues up, and clinicians feeling like there is nothing we can do to help?

EM: It’s not necessary to take a detailed past trauma history to create an environment that is receptive and responsive to their trauma. Oftentimes, it’s not a good idea to take a detailed trauma history; it could be very overwhelming for people who don’t have coping mechanisms, or who are actively using substances.

It’s not necessary to take a detailed past trauma history to create an environment that is receptive and responsive to their trauma.

That said, I think clinicians can look for markers of trauma to help guide treatments offered, and in our openness to understanding why patients are acting the way they are.

What are Markers of Trauma?

Markers of trauma are the health conditions that are highly correlated with recent and past trauma, including: heart, lung, and liver disease; obesity and diabetes; substance abuse and overdose; and mental health issues such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.

When a clinician is caring for a patient with any of these conditions, they may want to use a “trauma lens” and assume that a history of trauma may have contributed to these conditions; using a trauma-informed approach and offering serves to heal from past trauma along with traditional medical therapies may lead to better outcomes and experiences of care. There are also a number of behaviors correlated with having experienced trauma or having PTSD that are often attributed to personality disorders. These too can be considered “markers”, and include being reactive, easily triggered, easily offended or angered, withdrawn or disassociated.

That said, if a patient has a mental illness, is suffering from substance abuse, or has obesity and diabetes, there’s a very good chance that they had a serious traumatic experience(s). Among people living with HIV, the likelihood of significant childhood trauma is really high.

DEM: What can palliative care clinicians do when they return from Seminar, to change how they assess and support patients, in ways that are both evidence-based and safe?

EM: It is important to acknowledge that many providers and staff themselves have histories of trauma. Working with patients with such severe illness and such significant histories of trauma can cause vicarious trauma or else stoke our own histories of trauma. Conscious awareness of our own traumas helps us maintain a professional and therapeutic stance towards our patients with trauma. We can use guidelines (detailed below) for inquiring about trauma and past trauma in particular, which are not triggering or dangerous for our patients, and not overwhelming for ourselves.

The most important thing to do is to offer statements of empathy and support. And acknowledge that it’s really helpful that they had the courage to tell you.

In one final thought, I’d say there’s no emergency, nothing you need to do when a person reveals a past history of trauma other than hear it, acknowledge that you heard it, and thank the patient for trusting us with this information. With the revelation of significant past trauma, the most important thing to do is to offer statements of empathy and support. And acknowledge that it’s really helpful that they had the courage to tell you.

How to Inquire About Past Trauma

There are guidelines that should be followed when inquiring about past trauma. It’s important to recognize that the approach chosen is dependent on the resources, expertise, and patient population of individual providers and practices. The options listed below are included in a forthcoming publication.

Option 1: Assume a history of trauma instead of asking

All patients can be approached using a “trauma lens” that assumes that difficult life experiences may have contributed to current illnesses and coping behaviors. Regardless of whether or not a patient chooses to disclose their trauma history, referrals can be offered to onsite or community-based interventions that address experiences and consequences of past trauma.

Option 2: Screen for the impacts of past trauma instead of the trauma itself

Screen for symptoms of common conditions that are highly correlated with traumatic experiences, such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and suicidality, substance use disorder, chronic pain, and morbid obesity. These conditions are often “markers” for past trauma and benefit greatly from being addressed in a trauma-informed manner.

Option 3: Inquire about trauma using open-ended questions

Open-ended questions included in routine history taking allow patients to disclose any form of trauma they feel is relevant to their well-being. An open-ended script may look like the below example:

Difficult life experiences, like growing up in a family where you were hurt, or where there was mental illness or drug/alcohol issues, or witnessing violence, can affect our health. Do you feel like any of your past experiences affect your physical or emotional health?

Option 4: Use a structured tool to explore past traumatic experiences

Multiple validated scales exist to screen for past trauma. If a structured screening tool or process is used, carefully consider when, how, and by whom it will be administered, as well as who will have access to the information. Regardless of what tool is used and how it is administered, it is essential that the patient is able to discuss their responses with the provider in private.