Equipping Oncology Professionals with Core Palliative Care Skills

The benefits of palliative care concurrent with oncology treatment are well-documented: lower symptom burden, fewer emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and less caregiver distress.[1],[2] In short, higher-value cancer care. In fact, these outcomes are so consistent that both the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Cancer Institute recommend combining standard oncology care with palliative care for patients with advanced cancer or high symptom burdens.[3]Yet while the evidence is well-established, education in core palliative care skills for oncology professionals lags far behind.[4] Oncologists identify and document distressing symptoms reported by their patients less than half the time,[5] and themselves report a lack of training in discussing what to expect in the future in terms of achievable goals of care for their cancer patients.[6]

As health plans and health systems now work to maximize the value of the care delivered to the seriously ill, the integration of the core principles and practices of palliative care into routine oncology workflows is a prime opportunity to achieve better experience of care, better clinical outcomes and lower cost. We did some investigation to find out what is being done to capture this opportunity.

Palliative Care as the Path to High-Value Care

We already know that as health care systems adapt to value-based payments and risk-sharing arrangements, many organizations are investing in palliative care teams to improve the value of care for their sickest and most complex patients. Palliative care specialists are, for example, supporting the practice transformation needed in the new Oncology Care Model at Mount Sinai Health System, and are contributing to success under global budget contracts at Partners Healthcare.

But if all people living with cancer are to receive the support that reliably improves quality and reduces cost, it is not realistic, for several reasons, to rely on palliative care specialists alone. First, referral to yet another consultant for basic pain and symptom management and communication about care priorities undercuts the oncologists’ primary treatment role; second, there will never be a sufficient number of palliative care specialists to meet the expanding population need; and third, meaningful conversation and effective pain and symptom management are essential elements of standard oncology care.[7] High-quality cancer care therefore will require oncology professionals themselves to gain the basic palliative care skills that most did not receive in their training.[8],[9],[10]

Our investigations did find several efforts to instill core palliative care skills at leading cancer institutions.

…the integration of the core principles and practices of palliative care into routine oncology workflows is a prime opportunity to achieve better experience of care, better clinical outcomes and lower cost.

Communication Skills Training

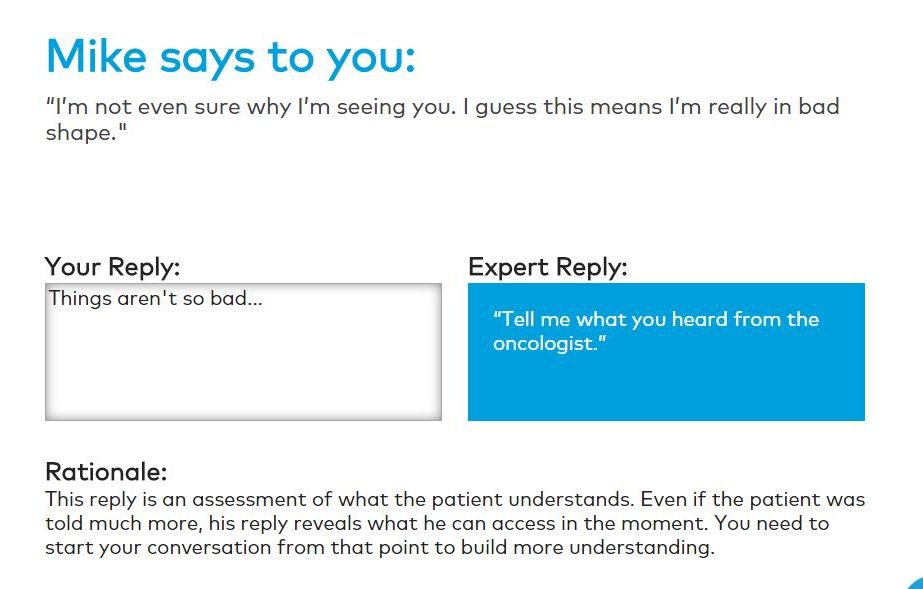

Most training programs have focused on communication skills, including the following:

At Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, communication skills training has followed a standardized modular curriculum for several years and is mandatory for oncology fellows, residents, and nurses. It is also one of the rare instances of a mandatory program for physicians and surgeons who are currently practicing.[11]

Systematic communication skills training for non-palliative care clinicians is a more recent undertaking at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, where Diane Portman, chair of Supportive Care Medicine, together with a psychiatrist colleague, secured funding to become Vital Talk facilitators in 2016. Over the past year, they have conducted several half-day Vital Talk workshops within their own organization, with a curriculum customized for Moffitt’s needs. The program is mandatory for fellows and open to residents, interested faculty, and nurse practitioners. Moffitt also delivers pain and symptom management lectures, mandatory for fellows, residents, and nurse practitioners, and voluntary for others.

At MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, TX, Daniel Epner and Walter Baile developed a communication skills training (CST) course for first-year medical oncology fellows, initially conceived as a series of monthly one-hour seminars. The curriculum was structured to overcome difficulty integrating training retreats into busy clinical schedules.[12]

While these programs have enabled improvements in patient experience, few have targeted practicing oncologists themselves. According to our interviews, efforts to mandate communication skills training for practicing oncologists are typically met with great resistance. As one educational program director noted: “We joke that all oncologists believe they are above average, and that is hard to overcome when you’re lobbying for mandatory training. Fellows and nurses are much more willing and enthusiastic learners in general.”

Dr. Yael Schenker, Director of Palliative Care Research at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, counters that many oncologists fully recognize the need for their practices to acquire primary palliative care skills, but for many, the most feasible way to achieve this is through nursing education. Dr. Schenker is conducting an NIH-funded randomized control trial of a care management intervention by oncology nurses, called CONNECT. CONNECT training consists of the following key components: addressing symptom needs, engaging patients/caregivers, providing emotional support for patients/caregivers, communicating with oncologists, and coordinating care. This comprehensive approach strengthens both communication skills and pain/symptom management skills among nurses, key contributors to any oncology team.

The CONNECT approach is not dissimilar to Aetna’s long-standing training for nurse case managers, many of whom work with cancer patients. Compassionate Care case managers receive extensive training not only in engaging patients and clarifying goals of care, but also in assessing symptom burden and discussing expectations for the illness. April Vallerand, PhD, Professor in the College of Nursing at Wayne State University in Detroit, MI, says that nurses trained in pain management can be powerful patient advocates, particularly outside of the hospital setting.

Routine Patient Reports of Symptom Burden

Recently published data from MSKCC (below) demonstrated that routine symptom reporting from cancer patients, not only improved the experience of care and quality of life but also significantly improved survival – presumably by relying on patients as early warning systems for changes in their conditions, and then ensuring timely clinician responsiveness via work flow re-engineering.[13],[14]

Florida’s Moffitt is experimenting with a similar effort driving primary pain and symptom management through patient-reported triggers. Dr. Portman’s team at Moffitt Cancer Center has developed a tablet-based application for patients to self-report their symptoms while in the waiting room. Patients answer a series of questions based on the widely-used and validated Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, and their scores flow directly onto the patient’s electronic health record, which then prompts the oncologist to review high scores and discuss possible interventions. The intention is to activate oncologists to ensure effective pain and symptom management.

Payer Role

While health care organizations are beginning to invest in the palliative care training needs of their oncologists, payers have an important role to play here, too. Health plans can require documentation of palliative care training for their network credentialing, or can provide financial incentives for completion of palliative care training. With the rise of alternative payment models for oncology, health plans can require that oncology practices demonstrate palliative care competencies and interventions as a condition of participation in the payment model, or at least as a condition to qualify for higher levels of shared savings.[15] Anthem and Blue Shield of California are already putting such incentives in place.

Training resources

As all these early adopters are demonstrating, equipping oncology professionals with core palliative care skills can be the most transformative and sustainable means of maximizing quality and value in cancer care. Resources are already available to help oncology practices. These include:

VitalTalk (vitaltalk.org). VitalTalk’s signature advanced communication skills course features cognitive mapping, deliberate practice, and just-in-time feedback. Results are immediate and significant and promote lasting improvements. As the Moffitt Cancer Center has demonstrated, VitalTalk’s train-the trainer program embeds communication skills experts within the local organization, thus sustainably expanding and deepening clinician skills.

Ariadne Labs’ Serious Illness Care Program (ariadnelabs.org). This program provides intensive training and workflow re-design, including triggers and tools to help clinicians initiate, record and subsequently review difficult conversations in the right way at the right time.

Center to Advance Palliative Care (capc.org). In addition to providing communication skills courses developed in collaboration with VitalTalk, CAPC membership offers health care organizations’ clinical staff unlimited access to a comprehensive curriculum in pain management, symptom management, dementia care, and more. Plus, there are downloadable resources such as symptom assessment tools and key phrases, and access to experts for guidance. CAPC is also developing customized learning pathways for oncologists, case managers, and oncology nurses to help health care systems quickly disseminate palliative care skills across teams.

For further discussion on topics regarding palliative care, please join us at CAPC National Seminar 2017and Pre-Seminar Boot Camp.

Citations

-

Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, “Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 2016; 316(20)

-

Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al., “Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial,” J Clin Oncol , 2016 33(13),1446-52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824

-

harmarajan KV, Wei R, Vapiwala N, “Primary Palliative Care Education in Specialty Oncology Training: More Work Is Needed,” JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(7):858-859. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0763

-

Buss, M. K., Lessen, D. S., Sullivan, A. M., Von Roenn, J., Arnold, R. M. and Block, S. D. (2011), Hematology/oncology fellows’ training in palliative care. Cancer, 117: 4304–4311. doi:10.1002/cncr.25952

-

Pakhomov SV, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Roger VL. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(8):530-539.

-

Daugherty CK, Hlubocky FJ: What are terminally ill cancer patients told about their expected deaths? A study of cancer physicians’ self-reports of prognosis disclosure. J Clin Oncol 26 (36): 5988-93, 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19029419?dopt=Abstract

-

Timothy Quill, Amy Abernethy, “Generalist plus Specialist Palliative Care — Creating a More Sustainable Model,” NEJM, 2013; 36813(28). http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1302093

-

Eskander RN, Osann K, Dickson E, et al. Assessment of palliative care training in gynecologic oncology: a gynecologic oncology fellow research network study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134(2):379-384.

-

Larrieux G,Wachi BI,Miura JT, et al. Palliative care training in surgical oncology and hepatobiliary fellowships: a national survey of program directors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(suppl 3):1181-1186.

-

Racsa, M. et al. Palliative Care Training in Radiation Oncology: A National Survey. International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics , Volume 93 , Issue 3 , S61 – S62

-

Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banieree SC, et al., “Communication Skills Training for Oncology Professionals,” J Clin Oncol, 2012; 30(11):1242-7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6184

-

Epner, D, Baile, W, “Difficult Conversations: Teaching Medical Oncology Trainees Communication Skills One Hour at a Time,” Academic Medicine, 2014; 89(4), 578–584. & Interview with Daniel Epner, MD, May 2017.

-

Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, Scher HI, Kris MG, Hudis C, Schrag D. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. JAMA.2017;318(2):197-198. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7156

-

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

-

Fields, T. K., “The Carrot or the Stick? Integrating Palliative Care into Oncology Practice,” The American Journal of Managed Care, 2017; 23(7).