What You Can Do To Improve Quality Right Now

I had the privilege of visiting palliative care colleagues in Melbourne, Australia in February of this year. Not only did they share some great book recommendations (Songlines by Bruce Chatwin – which includes this quote comparing western to Australian aboriginal culture: “We give our children computer games and guns…they give their children the land.”) and fantastic wine and food that rivals that in my home town of New York City, but also a breathtakingly simple way to monitor quality of palliative care during your weekly team meeting.

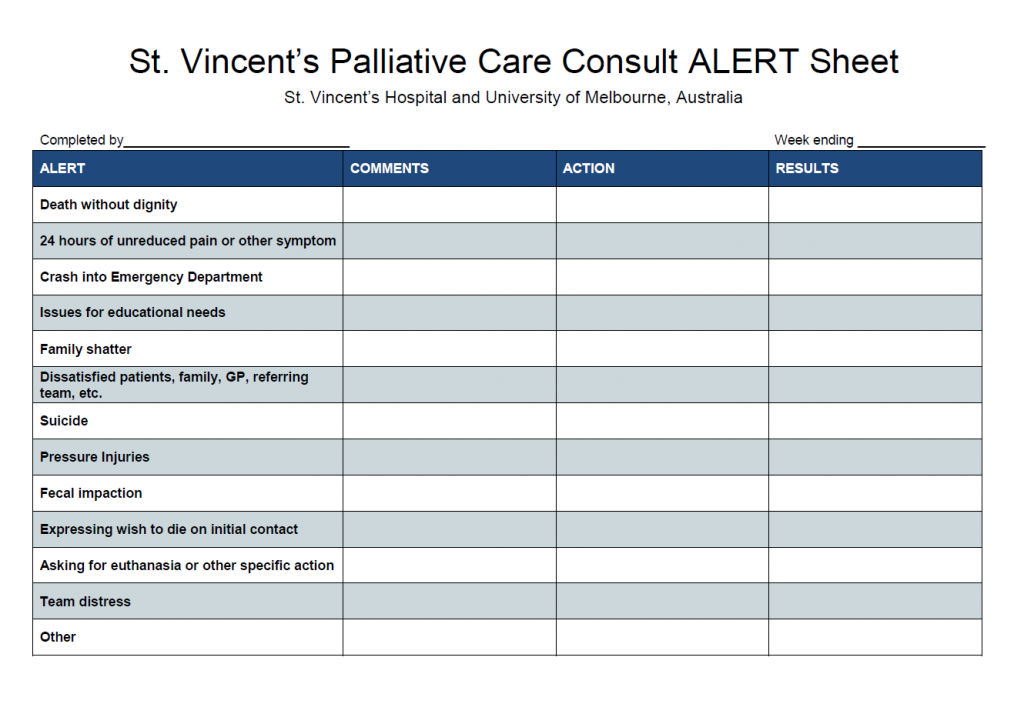

I observed the weekly palliative care team meeting during my visit. After “running the list” and discussing each patient on service with the whole team, Dr. Jenny Philip pulled out the spread sheet below and asked everyone if they had observed any of the following among the patients they had cared for:

- Uncontrolled pain and symptoms for >24 hours

- Fecal impaction

- Dissatisfaction with the team’s care on the part of patients, family members, colleagues

- Occurrence of requests for a hastened death

- Emergency room “crash” admissions

- Team distress

- And others

If such an occurrence was noted, specifics were recorded and the team leader then developed a plan of inquiry, root cause analysis and remediation.

Not only does this process allow assessment of the prevalence of these issues (for example, among tens of thousands of patients served by palliative care over a one-year period, the frequency of requests for aid in dying was less than 1% ), it creates a basis for ongoing quality improvement. The screen identifies early warning signals of system structures and processes that are failing patients and their families, as well as professional knowledge or skill deficits that are actionable and amenable to improvement. Dr. Philip wrote to me last week with an example of the impact of the screening tool at her teaching hospital:

Perhaps one example of the quality feedback loop is that we had a couple of instances with some junior colleagues of another unit whereby their patients and families appeared to be distressed and unprepared for their rapidly deteriorating condition. As a response, and with the buy-in of their heads of unit, we instituted some targeted communication skills training for the registrars. This has been useful both for satisfying the objective of improving their communication with patients and families, but also as a relationship building exercise with the unit, specifically, and the hospital more broadly, which is keen to expand this teaching.

Changes in prevalence of these issues over time also provide directional guidance to the team and to the health system. If, for example, an uptick in the frequency of fecal impaction is noted, the team can analyze the circumstances: How many of these patients were on opioids? How many had an appropriate bowel regimen prior to the impaction? Was the issue concentrated on certain hospital units or patient groups? Do we need staff re-training? Should we build accountability for this outcome into our system/hospital/team metrics? Would an order-entry algorithm for bowel regimen intensity based on recorded frequency of bowel movements be worth piloting?

While we are waiting for clarity on what we will have to do in terms of quality reporting under MIPS and MACRA, this straightforward and efficient process could actually do more to improve quality than any advance directive checklists. If people try this, please let us know how it works. I’d love to see the field begin to standardize the use of such tools as we work at the system level to protect all seriously ill patients from unnecessary suffering and harm.